Man, I’ve always wanted to use that as a title for something. I love etymology. I find it very fascinating to peel off a prefix and study it, call to mind its other associations. Let’s take ‘trans-’ for instance, since we’re on the subject, or about to be. Transformation, transportation, transcendence, transgender, transhuman - it evokes movement across boundaries, evolution from one form, place, state, gender to another. So transhumanism, then, begs its own question simply by the way it’s constructed: if away from ‘human’, movement into what?

It’s a concept I find very fascinating. I’m a bit of a transhumanist myself, though my interest has mostly been limited to the academic, and the fictional. I can’t boast the commitment of the cyborgs, the digital paradise groups, the eccentric types working towards fusion with capital-T Technology writ large, whatever form that may or may not eventually take. Incidentally, you should read Mark O’Connell’s sublime To Be A Machine for a trip into that world.

But that doesn’t mean my interest in the subject is completely removed from my own perspective, or experience. I know all too well the boundaries of my flesh, and I have loathed and lamented its shape, its confinement, its total disconnect from my own internal reality for my entire life, in some form or another. What I know now to be the thoughts of a transgender person, I misconstrued as an urging towards transhumanism in my younger years. I knew I wanted to be something I was materially not; some sort of cybernetic or digital being seemed as good an alternative to ‘A Man’ as any other, at the time.

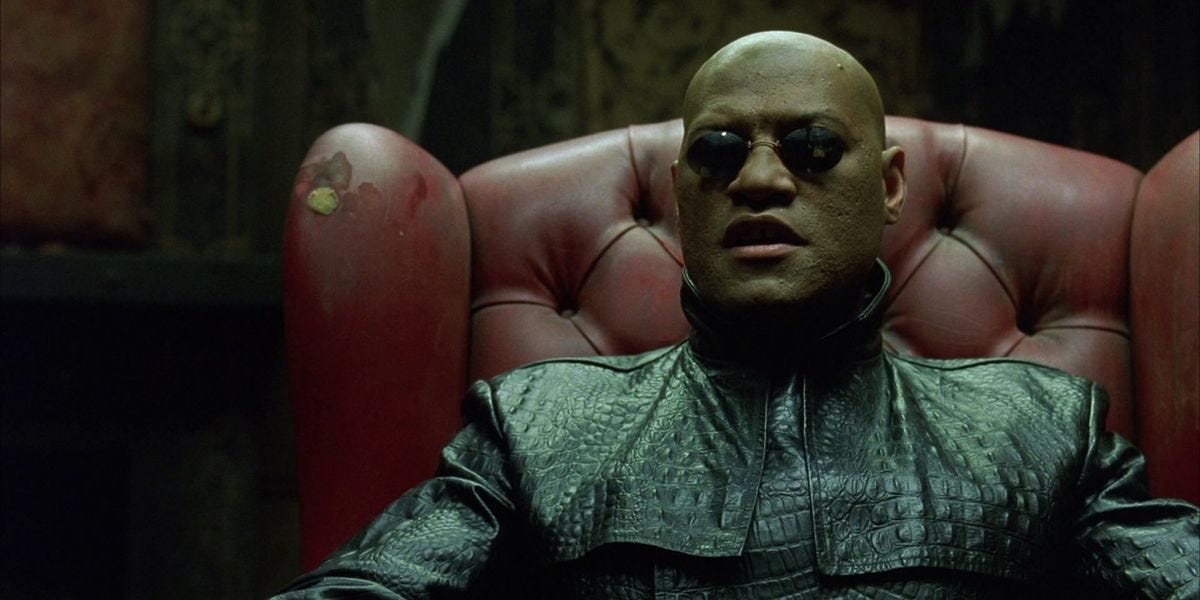

Even so, transgenderism and transhumanism aren’t divorced from one another; very much the opposite, in fact. One of the most well-known transhumanist texts, the Wachowski sisters’ The Matrix (1999), contains a monologue woefully appropriated by a social movement better left unnamed; nonetheless, the sentiment of it may ring familiar to many trans people. As Morpheus puts it during his introduction:

You’re here because you know something. What you know you can’t explain, but you feel it. You felt it your entire life: that there’s something wrong with the world. You don’t know what it is, but it’s there, like a splinter in your mind, driving you mad.

We strain at the limits. We see what flesh we inhabit, and we know what we are somewhere deep within that, and the disconnect is inescapably uncomfortable. The overlap is directly acknowledged within the arc of Beth Bisme-Lyons in Russell T. Davies’ Years and Years: she ‘comes out’ as trans to her parents, who are supportive of her being transgender, until they realise that’s not what she meant at all. She’s telling them she wants to become a machine. But her explanation leaves enough room for ambiguity all the same. There’s something wrong. The flesh and the ghost within it are irreconcilably misaligned.

“More Human Than Human”

Transhumanism isn’t strictly limited to fusing with AI constructs or grafting on bionic limbs, of course. If anything, that’s merely the most recent incarnation of an ancient dream that we could chase all the way back to the caves if we knew where to look. All technology is, in some way, a substitution for organic lack or inadequacy: from the pacemakers that substitute a missing regularity in the heart, to eyeglasses compensating for impaired eyesight, to the plough that readies the earth for seeds better than human hands can, to the wheel that moves matter over land better than our feet do. ‘We are’ - as Donna Haraway famously put it in A Manifesto for Cyborgs (1985) - ‘all chimeras, theorized and fabricated hybrids of machine and organism.’ This is more posthumanist theory than transhumanist, but they’re branches of the same tree. Straining against the boundaries of our limited selves is what we do, and what we’ve always done.

What are sex and gender if not merely more boundaries to broaden?

There are certain elements in society who do not like this kind of radical thinking. There is a belief - and who am I to say it’s not an understandable one? - that we have boundaries for a reason. Personally, I would say we push those very boundaries for a reason too, but this isn’t really intended to construct an ideological argument, so let’s not get carried away.

What matters is that the impulse is there, and it’s as natural as the very matter it rejects. It is the fallen angel meeting the rising ape, to borrow a Pratchettian analogy.

Body/Horror

I would never commit the injustice of suggesting that transhumanism only belongs to sci-fi, of course. There’s all manner of means beyond the scientific for the frontiers of the body to be pushed in the realms of fiction; when we’re talking about the body, we might turn our lens to horror. The Gothic (from whence modern horror takes its roots) is fascinated above all else with the transgression of borders and boundaries: the turning insides out, the putting outsides in, crossing thresholds be they geographical, moral, spiritual, social, physical, anything.

Eldritch horror is great at this. Bloodborne is singularly excellent. A fascinating piece from a few years ago draws direct connection between Bloodborne and transhumanism, and whilst I am by no means convinced that Bloodborne is a truly ‘cyberpunk’ text, it is absolutely and unmistakably a transhumanist one. The body is a site of carnage and horror in Yharnam and its surrounding environs, the city plagued by beastmen, snakes erupting from bodies, deformed insect-people - but simultaneously, it contains within it the promise of ascension and transcendence if one is willing to sacrifice enough.

The horror of having a body isn’t a fictional idea to many of us, maybe even any of us. Cis or trans, who among our species has not felt tormented by the inadequacy of flesh, seen our bodies as too much or too little for something ineffable deep within, when confronted by ourselves in the mirror? Many of these problems are social, true - but just as many are innate and psychological. Many of them stem from the real self held in our minds as a tangle of thoughts, experiences, memories, opinions; that thing (whatever we might call it) rages in its way against the bars of a cage of meat and bone.

It is this impulse, this inadequacy, that drives the transhumanists of Bloodborne to seek incarnations beyond the anthropomorphic, to find a home for themselves in less meagre a form - and the same impulse that drives the transhumanists of science fiction (and the real world) to struggle against the borders between flesh and machine, believing or hoping or knowing that our great internal unrest will be soothed by a disavowal of our present physical reality. It is this same impulse that drives transgender people to change the outside to better fit what it contains.

What does transhumanism tell us about being trans?

This all fascinates me greatly, and personally. But it really doesn’t have to be a navel-gazing exercise; quite the opposite, in fact. Liberating ourselves from the confinement of a prescribed material reality should free us from a forced introspection, too. Bloodborne’s ‘eyes on the inside’ certainly represent the desire to know ourselves better than we can with our perspective fixed firmly outwards, but that’s merely a first step to attaining a greater understanding of the infinite world outside ourselves. Anyone embarking upon a journey of any length or import should familiarise themselves well with their vessel.

I raise this point because I do sincerely regard the binary system of gender (and sex, while we’re at it) to be a prison. It’s an artefact of our primordial heritage, putatively useful at one time for figuring out which ones in your tribe got pregnant and which ones did the impregnating, but that’s hardly the be-all and end-all of existence anymore. It’s a relic insiting upon itself, one which has shackled people to roles they would never choose for themselves, and one which is raised like a whip to crack and oppress all born under it.

Transhumanism poses a simple question, and when you get right down to it, being transgender asks the same one: “why am I this way, and do I have to be?” That simple question cascades into countless others, each one decoding and deconstructing another societal assumption, finding it empty, and discarding it.

It’s about escape. It’s about rejecting facts that exist for their own sake, and pulling back the curtain reveals the wafer-thin artifice of the whole facade. When you question things in this way, when you begin to seriously interrogate the whys and wherefores of so many of our basic assumptions, it’s truly astonishing how much begins to fall apart. And once you see behind the curtain, you can go there yourself. You can take control. You can ascend, in some sense, to a new way of being.

Where’s the pink white and blue?

I suppose what irks me, if anything does, is that this is all very, very fertile thematic soil, and I’m not seeing a lot of saplings. I won’t pretend I have a faultless panopticon for queer sci-fi literature, that my finger is expertly placed on this very particular pulse. But surely I shouldn’t have to look terribly hard to find something so deeply relevant to the world we live in today.

I know, I know - ‘be the change you want to see in the world’. Hey, I’m doing my part: I’m chipping away very very slowly at my own little queer sci-fi novel in the space between churning out unsolicited thinkpieces like this one, don’t you worry about that. And it would be remiss of me - as I lament my own myopic inability to find queer fiction of my extraordinarily specific tastes - not to mention that there is non-fiction on this topic, including this excellent Medium piece on the trans-ness of cyborgs I found while digging up material for this post. So, you know, these fields aren’t entirely fallow or anything - but that by no means indicates there isn’t a lot more to be done.

This is not a plea for media recommendations, unless you have any, in which case my god it absolutely is and you must send me them please. Rather, it’s a facet of the transhumanist philosophy as a whole (and cyberpunk literature, its natural home, in particular) I personally feel is ignored more than is deserved. Like, speaking of etymology - you know the word ‘android’ means ‘like a man’, right? How is one of the most common and recurring terms in science fiction gendered in such a reductive and asinine way?

I’m a little dubious on the prospects of the real-world transhumanist movement, since a decent swathe of it seems to be the sickeningly wealthy investing in cartoonish schemes for immortality. That’s… their prerogative, I suppose, but it feels a little less admirable to claw back a few more years of making the world worse for everyone else in it than the other prospects the field has to offer.

But still, this area speaks to me as much now as it ever has. ‘Luminous beings are we’ - opines the swamp-dwelling war crime frog of Empire Strikes Back - ‘not this crude matter’, and for all his many faults, Yoda was completely right about that. The light, the ghost, the spirit of me wants more than the meat can offer. In the face of the mind’s unerring need for more than is freely given, it is the business of the flesh to keep up or be left behind.