Fear & Hunger Is Exactly My Kind Of Fucked-Up Nonsense

'The thought must have crossed your mind at some point. The thought that you'd delved too deep. The thought that this would be a one-way trip.'

[Mild spoilers for Fear & Hunger and Fear & Hunger: Termina follow. These games contain depictions of drug use, self-harm, suicide, body horror, sexual violence and extreme gore; this piece only contains images pertaining to body horror and sparing references to the rest]

I got really into Fear & Hunger this year. Like, really into it, to a degree I don’t get into for a lot of things. In over my head, dredging up every single scrap of lore, watching multiple playthroughs on Youtube, refreshing the ‘New’ filter on the subreddit, trying my hand at some fanart, getting absolutely everything I could out of it. Everything short of, um… actually playing either of the games.

Well, to be fair, it wasn’t the horror that put me off this time. I’m mostly jumpscare-averse, and Fear & Hunger’s horror is much more of the ‘crushing atmospheric dread’ and ‘violent, grotesque body horror’ flavours for which I have a much keener tolerance (and a morbid preference). This time, it was the difficulty - always the first or second thing to be mentioned when this game comes up, either ahead of or immediately after the relentless and severe misery of the setting. The thought of losing hours and hours of progress to a coin toss has kept me at arm’s length for the last half a year or so, but my fascination with the games has endured nonetheless.

I just want to ramble about it. Is that cool? Whatever, it’s my blog, and I get to choose the hyperfixations.

Too greedy, and too deep

Let’s get right into it, then: what is Fear & Hunger? The first game is an RPG Maker MV project developed almost entirely solo by Finnish indie developer Miro Haverinen of Happy Paintings, taking the top-down RPG interface of your early Final Fantasy-s, your Undertale, your Earthbound, etc., and the turn-based combat of the same. Its unique selling point is its emphasis on harrowing, nail-biting tension and dread cultivated by the two titular factors: your avatar must balance battles against horrifying, sadistic enemies and management of extremely meagre resources including physical and mental health, light, consumable items and - of course - food. Mechanically, it’s all simple enough, but there are some great extra flourishes to be found here. For example, individual limbs can be removed inside or outside of combat… from the enemies, or from you. A swing from a meat cleaver or the jaws of a bear trap hidden in the shadows might cost you a leg. Sometimes, an infection can turn septic, and you’ll have to take off a gangrenous limb yourself with a bonesaw, utilising some of the most exquisitely uncomfortable sound design I’ve ever heard.

Needless to say, lost appendages stay lost… but the game persists. Food might run out, but you must continue. Your mind might break, your last torch may falter, your allies - found few and far between - might fall in battle, but you yourself must carry on until death or victory arrive at last. It’s a game about endurance in impossibly challenging circumstances. What else would something with this title be about?

You’re going to die a lot here, in the Dungeons of Fear and Hunger, but that’s okay. Next time, you know when to guard against that attack. Next time, you know to save that healing vial. Next time, you know where that rusty nail is. Next time, next time, next time, until the unscalable wall is broken before you.

So… what are you doing down there in the first place?

The mission is a man

The answer to that question actually changes around a certain point, and I’m going to use this opportunity to drop a big old ***MID-GAME SPOILER WARNING*** here because a lot of what makes this game stand out is in the strange and hypnotic development of the game’s plot. If you want to experience the story totally un-spoiled, then stop reading here and go get Scared and Peckish, damn it! Or I can recommend some playthroughs if you’re similarly inclined to myself.

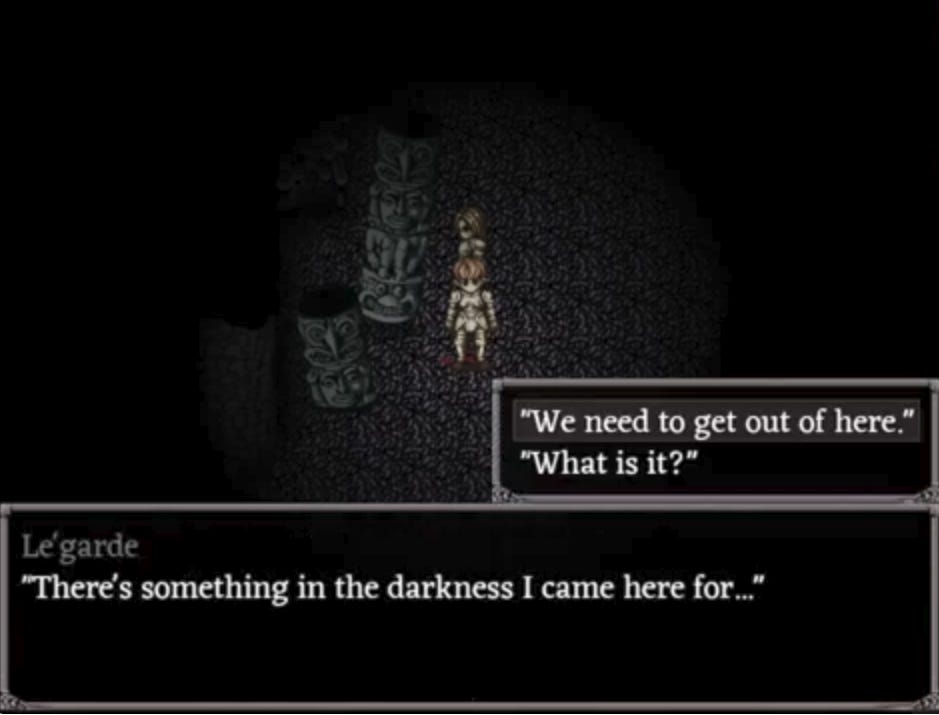

Whichever of the game’s four playable characters you begin with, your objective is the same: find the mercenary leader Le’Garde somewhere in the Dungeons of Fear and Hunger before he dies. Your characters motivation for finding him and the details of what they intend to do with the man vary, but that objective does not.

On your first attempt (and with many deaths undoubtedly already behind you) Le’Garde will almost certainly be dead when you find him. This is because he’ll be executed by the denizens of the dungeon 30 real-world minutes after your arrival on the surface. The strategy, then, is to get there faster next time.

So: you perfect your route to his cell, you refine it down to this impossibly tight deadline, and hooray! He’s alive! A little worse for wear, but intact. Time to get the fuck out then, of course! Wait, Le’Garde, what are you looking at-

This, in a sense, is where the game really begins. It’s not about getting to Le’Garde’s cell anymore: it’s about getting all the way to the bottom of the dungeons, to Ma’habre - the city of the Gods - and the primordial domain beyond it where mortals and ancient entities entwine. In other words, it all gets a bit Dark Souls, story-wise.

Now we’re really fungering

From here on, the enemies get a lot stranger, the fights get a lot tougher, and the stakes get a lot higher. Still, you are nothing more than a tenacious adventurer equipped with no resources more mystical than your cumulative experience from a hundred failed attempts and whatever scraps you can find lying around the dungeons.

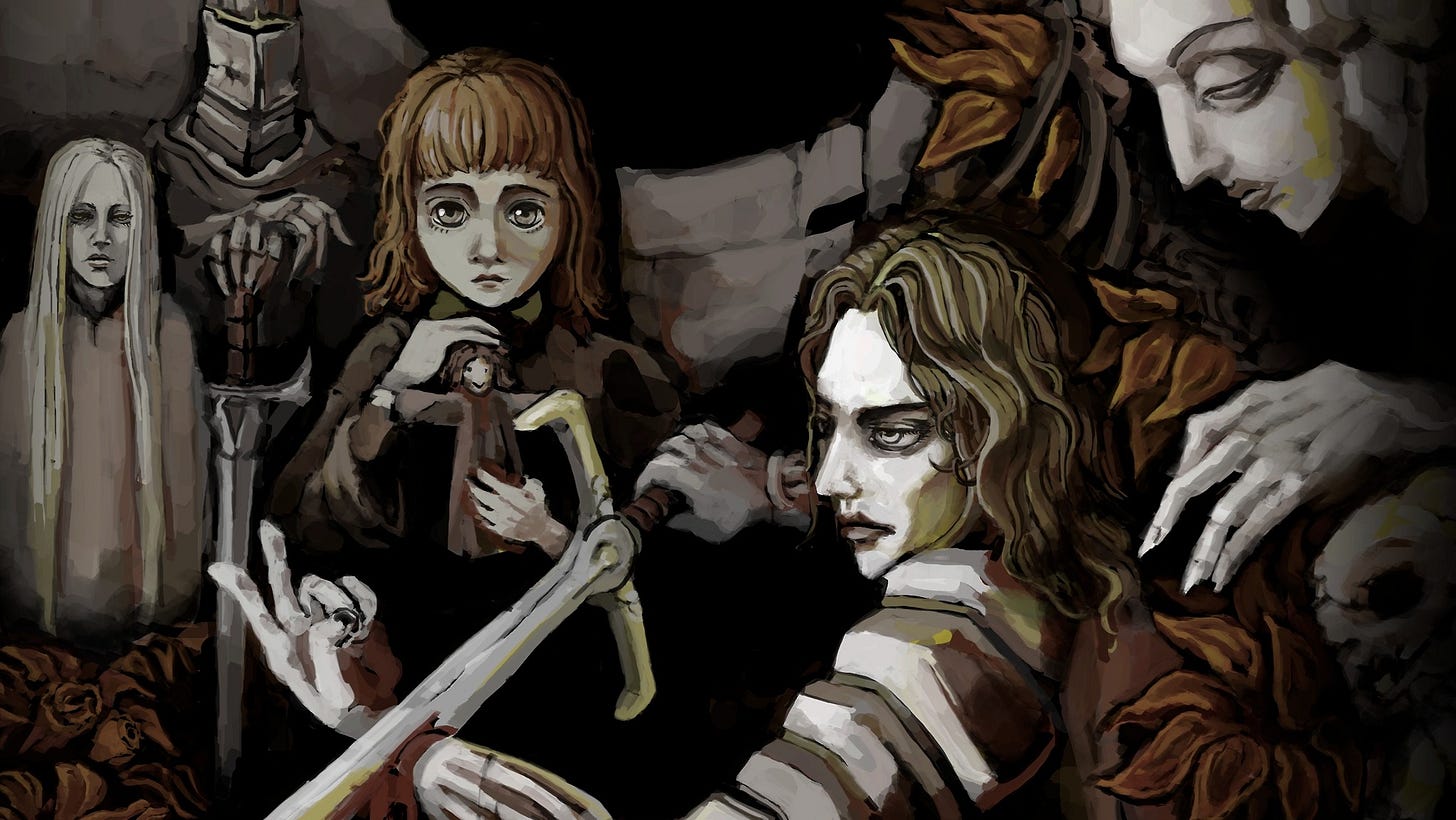

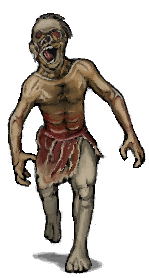

Ahead of you, there are mad gods, horrific abominations, and this fucking thing.

So too must your methods be unorthodox, your desperation limitless. You will have to do whatever it takes. Wield a cursed sword that whispers in your mind for the blood of your allies; bind yourself forever in cursed armour that bites your flesh with every step; perform a gruesome rite of sex and union on a ritual circle to combine your strength - and your body - with a party member. In Fear & Hunger, absolutely nothing is sacred. You can draw whatever lines in the sand you like; the game will smirk and patiently wait for you to cross them, knowing you have no other choice.

Maybe this is what fascinates me so much about it: the scale of the depravity. Haverinen goes places many devs wouldn’t touch with a barge pole, for better or worse. I’m quite relieved he seems to have ‘grown out’ of some of the more crass elements of this for the sequel without compromising on the bleakness, as this shows an important degree of self-awareness and a great talent, to make such compromises on content without sacrificing tone or quality. We don’t need to list off every instance of tastelessness in the first game (around sexual violence in particular), but suffice it to say there’s a lot, and Termina - the game’s follow-up - is able to do just as much (or more) without it.

You’ve met with a terrible fate

Now let’s talk about that sequel, actually, because as much as the first game’s tone, atmosphere and designs engrossed me, Fear & Hunger: Termina is absolutely a cut above in every way.

The most notable improvement is to the characters: although Fear & Hunger had some interesting dynamics, the protagonists weren’t altogether rich. Hell, Le’Garde is so nakedly just a clone of Griffith from Berserk, their names are used pretty much interchangably in the fan community. He’s a dangerously ambitious and charismatic mercenary captain you rescue from a dungeon, and that is not even where the comparisons end. Like, come on.

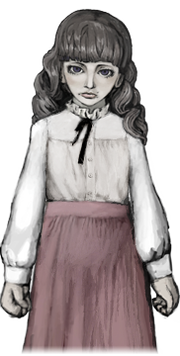

Termina fixes that outright. Currently, eight of the fourteen ‘contestants’ in the titular Termina festival are playable, and they’re all interesting in their own right (though some more loveable than others). Levi is a former child soldier on the lam after deserting the front lines, nursing a heroin addiction adopted to cope with the horrors he’s seen. Olivia is a botanist constantly living in the shadow of her much more successful twin sister, with a spinal ailment necessitating the use of a wheelchair (that’s not a character trait itself of course, but in a game like this it has very interesting effects on mechanics). Certified Good Boy™ Marcoh is a street thug and boxer who found himself dragged into the criminal underworld by poverty and blackmail. Fan-favourite (and my favourite) Marina is an occultist, born male and raised as a girl to spare her from the tradition of sending boys to become Dark Priests of her religion.

On top of the fantastic variance of their backgrounds and motivations, their dialogue is drenched in personality, with Marina herself prone to sardonic jokes and a kind of tongue-in-cheek nihilism occasionally betrayed by moments of earnest passion. We also learn that even though her feminine ‘disguise’ was initially a matter of safety and practicality, she actually feels much more comfortable presenting as female.

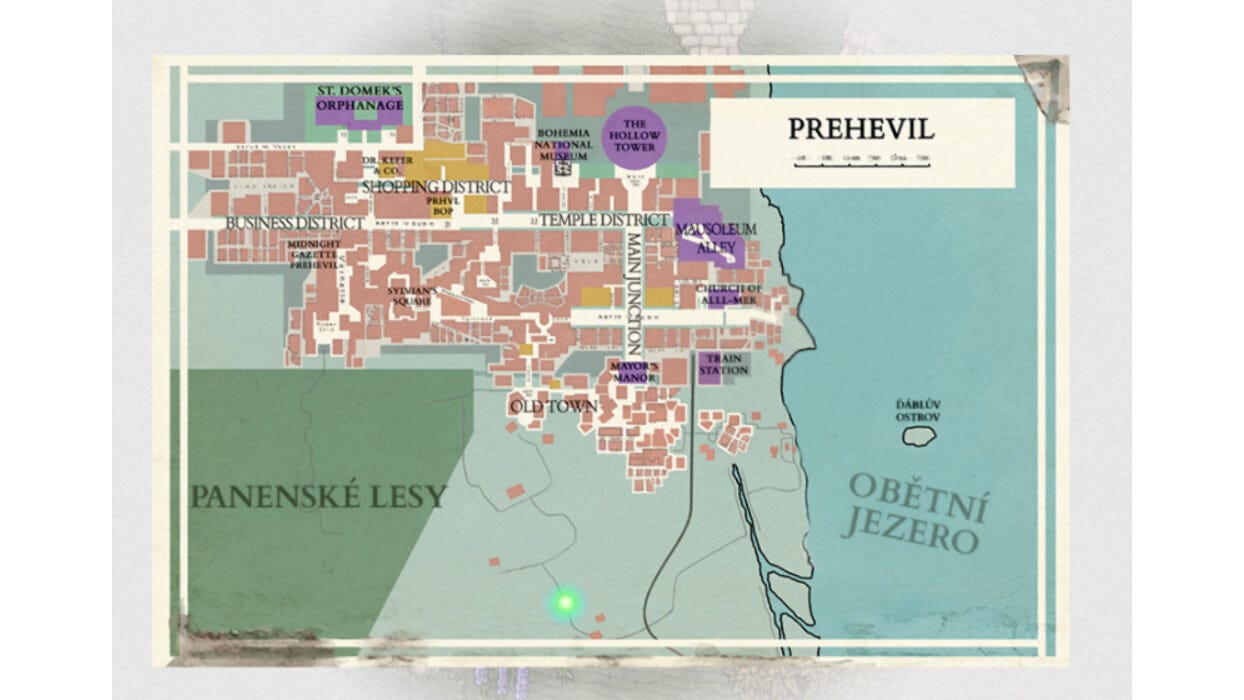

This game leaps forwards around 400 years from Fear & Hunger into the mid-20th century era of this alternate Earth, a kind of parallel history where the effects of ancient gods and contemporary mysticism are more sharply pronounced, yet technology and the movements of history march to a similar beat. The one thing the contestants of the ‘festival’ have in common is arriving in Prehevil (analogous to real-world Prague) on the same train, and being unwittingly drafted into a death game for the amusement of the trickster moon god, Rher.

That’s right: it’s a classic battle royale. Fourteen strangers enter, and only one may ascend the Hollow Tower to receive their dubious reward after the bloodshed. Like Majora’s Mask - the similarities to which it would be very hard not to notice - they only have three days to do it. If they don’t… well, that’s where one of my favourite aspects of this sequel come into play.

‘There is nowhere for you to hide; the hunter’s moon is shining’

If Fear & Hunger is predominantly Berserk/Dark Souls inspired, the overwhelming inspiration for Fear & Hunger: Termina has to be Silent Hill. And you knoooooow a bitch loves Silent Hill. The foggy city is infested with barely-human monsters, overridden with gore and delapidation at every turn, occasionally giving way to a shadowy Otherworld with a tenuous connection to reality.

Fine, that’s all good - in fact that’s a great basis to work on - but what’s really Silent about this Hill is ‘moonscorching’.

The mutations that have befallen the people of Prehevil haven’t come from nowhere, but rather are produced by Rher - the moon god - as a sadistic mechanism for sustaining the festival and punishing non-participation. The depth and variety of monster design on display in Termina is nothing short of astounding: even with the mostly-static 2D art afforded by RPG Maker’s engine, Haverinen is able to create horrors that fill the imagination to the brim. Take a basic enemy encountered early in the game, shown below:

This is, for all intents and purposes, a trash mob. But his design tells us so much with so little. His hands are flexed into bestial claws, his face mangled beyond recognition, teetering on the border between man and monster. Dialogue with any moonscorched Prehevilians early enough in the messy process to retain higher thought reveals that it manifests in many of them as an itch under the skin, and so many of the ones we find have torn that skin away from themselves to relieve the discomfort - shown above with the flap of flesh hanging from the waistline.

This is fantastic design work, and it’s the very tip of the iceberg. Elsewhere, ‘marriages’ (unions of two or more creatures into one through sexual rituals) etch the stories of their own creation into their very names and forms, including the Platoon, an amalgamation of all the soldiers in its namesake unit, and the Centaur, whose name explains it about as well as I care to think about.

The citizens of Prehevil aren’t the only ones basking and baking in the moonlight, though. Like I said, that three day time limit isn’t just for show.

‘Something is moving inside you…’

Each character you’re not currently playing as has a set time in the three day cycle (including Day, Evening and Night every day, for nine time stages total) where the moonlight will overwhelm them and they’ll transform into a monstrous version of their former self. These designs tend to reflect some element of their story, their psychology, their design, or so on, making them absolutely fascinating for close scrutiny. Let’s take one of my favourites: journalist Karin Sauer’s moonscorched form, the Valkyrie.

Aside from the art being fucking gorgeous, this design vividly evokes the way Karin sees herself. Karin isn’t just any journalist: she’s a war reporter, getting into the hidden politics behind the action to expose the machinations of corrupt leaders on the public stage. The name ‘Valkyrie’ of course refers to the battlefield angels who would escort the honoured fallen to Valhalla: those soldiers shown riding atop her back. As a war reporter, she sees her job as one honouring and avenging the fallen soldiery, and so the moonscorching twists her into a monstrous parody of that self-serving image.

Elsewhere, Levi, Marina and Olivia’s moonschorched forms contain enough psychological nuance to their designs to make me profoundly sad while retaining that sheer horror. It’s masterful. It’s poignant. It’s Silent Hill as fuck.

Answering the call

So, confession time: I have actually played this one. I know, I know, that’s not like me, playing a game in which I have a fanatical - some may say obsessive - interest. But there was only so much I could scratch the itch through vicarious enjoyment; I had to break the skin eventually.

I’ve played a few hours, which anyone will tell you is not enough to get especially far, even with the enormous benefit of knowing all the game’s tricks and traps ahead of first exposure. The initial experience has been about what I expected. It’s fucking frustrating, and sets my heart on edge to make any progress and know that it’s not enough to warrant a save, that I have to keep pressing forwards with the weight of all my achievements so far on my back, threatening to collapse into so many tears in rain the moment a random mob cuts me down. But nonetheless, I am really enjoying it. I feel the hooks setting in, that strange magnetism that compels me to start the game up again the moment I close to desktop.

In a way, I had wondered what it was that compelled people to keep picking these games up when the experience beat them down so thoroughly. Really, it’s simple: it just comes back to that question of endurance again. You want to give up, but you can’t. There’s still work to be done, a dungeon or town to be explored, characters to meet, rituals to perform, enemies to whittle down. Maybe that’s what Fear & Hunger really means - the fear of death at a moment’s notice, and the hunger for more that drives you inexorably on beyond the threshold of defeat.

Or something like that. But for now, I… am going to get back to playing.